Part One – Traveling the National Road

The origins of the National Road (also known then as the Cumberland Road) go back well before the birth of our nation. Other roads like Braddock’s Road and Forbes Road had gone before, but the National Road was to be a different project altogether. Unlike the others, it was not to be a military road, but one conveying families to a new life out west. It was under President Thomas Jefferson that the first plans for the National Road began to take shape. While funding was eventually withdrawn from the Road so that it never went further than Vandalia, Illinois, in its time it was critically important to westward travel and expansion. It was not until 1850 that Indiana completed its intrastate segment.

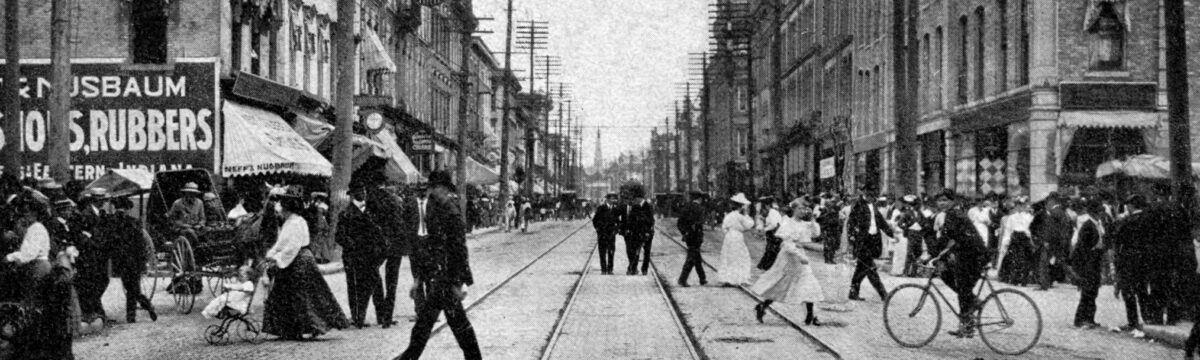

From the last of March until the first snowfall, the road was filled with wagons in a constant flow west. Richmond was one of the rare Indiana towns that was already in evidence before the road came into being.

Before the National road was built in Indiana, Robert Morrisson, the founder of the Morrisson Library and one if its foremost citizens, was behind the laying of a gravel road from Richmond to Dayton, Ohio. It was known as the “Richmond and Short-Line Pike.” This short span, with the exception of one mile between Clawson’s Tavern to the Ohio state line, was adopted into the National Road.

In 1830, the National Road became the first U.S. road to be resurfaced by the macadam process, a method pioneered by Scotsman John Loudon MacAdam. This process, simple yet effective, utilized a single layer of very small angular stone compacted in shallow lifts. Afterwards, a binding layer of fine dust was laid down and rolled, to further compact the road. This method is still used on country roads today.

In the beginning, however, the road was not at all pleasant to travel on and was full of the stumps of trees that had been cleared, mandated by legislators to be no more than fifteen inches at height. This made a very uncomfortable and bumpy ride! Mrs. Elizabeth Baird speaks of where often there were many stumps in the road, just low enough for a wagon to pass over. “There were many stumps in the streets…and as they were covered with snow, it was an easy thing to hit one… The next morning we again took an early start – so early that the stumps in the road were no more visible than the night previous. I was thrown against a stump and one arm was hurt though no bones broken. The pain from the injury however was severe. I was carried into a little hut were some people were just rising and placed on a bed which some very untidy folk had just vacated. I would have preferred the floor.” In the swampiest places, the road was a corduroy road, which is, made with logs laid perpendicularly across the road preventing wheels from being mired in the mud. Sometimes the stagecoach lost a wheel or became mired in the mud, in spite of the best efforts of those who laid the corduroy roads. In this case, the women and children were compelled to sit by the side of the road and await the men’s efforts to rectify the situation.

In spite of the macadam method, federal funding for the upkeep of the road became lax. President Martin Van Buren himself, traveling on the National Road on a campaign bid for a second term in office, discovered in Richmond what the locals thought of his views of limiting funding to the road so that it lapsed into “a dissipated sludge of tree roots and mud holes.” This story comes from The Old Pike – An Illustrated Narrative of the National Road by Thomas B. Searight “When Martin Van Buren made his trip through Indiana, many persons denounced him as an enemy of the National Road and someone in Richmond, to inflict chastisement upon the distinguished statesman for his supposed unfriendliness, sawed a double-tree of the coach in which he was traveling nearly through, and it broke near Mansur’s axe-shop, causing Mr. Van Buren to walk to the top of the hill through thick mud. The author of this mishap to Mr. Van Buren subsequently boasted that he had put a mud polish on Gentleman Van Buren’s boots to give him a realizing sense of the importance of good roads.”

Perhaps the memoires of the journey by Louie Beste provided the most amusing example of how children have evidently not changed too much in the last two hundred years: “How delightful we thought it the first five minutes! Eleven children packed in straw, with carpet bags and dressing-cases filling up the crevices, and a canvas awning over our heads! …In a very short time, complaints and murmurs began to arise from all parties. ‘How the wagon jolts!’ cried one: ‘How burning hot the sun is through the top!’ exclaimed another: ‘How uncomfortable it is not to have seats!’ said a third, moving impatiently.”

In 1926, the National Road became part of U.S. 40, and it is still an important part of Wayne County, Indiana travel.

— Gretchen Brown

Sources:

I, Beste by Louis Beste

The Old Pike – An Illustrated Narrative of the National Road by Thomas B. Searight

Stagecoach and Tavern Tales of the Old Northwest by Harry Ellsworth Cole and Louise Phelps

The National Road by Philip D. Jordan