Prairie Schooners – Moving Vans of a Bygone Era

Pictured is an old Conestoga wagon housed at the Wayne County Historical Museum. This wagon is not from the area, having been brought from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, yet it is not unlike many of the wagons that rumbled through Richmond on the National Road soon after it was built. Wagons, both for freight and the transportation of families overland passed through Richmond in the early history of the Road, sometimes one hundred and fifty in a day. The first wagons would not have rumbled through Richmond until 1827, as the roads were not yet fit for wheeled vehicles.

The Conestoga wagon was only one type of covered wagon. Most wagons that made the westward journey were mere farm wagons, upon which a frame and canvas had been erected. The Conestoga was a heavy freight-carrying wagon that originated in the Conestoga region of Pennsylvania around 1725. It didn’t get much use on the prairie, but across the Appalachians and on the National Road, it was a common sight. If we were to follow a family traveling from North Carolina to Richmond, at the dawn of statehood, we would see a far different journey than would be made by a family moving today.

Their wagon might be drawn by as many as six horses and could carry loads up to eight tons! In spite of this, it had the grace of a ship, curved at the bottom, rising at each end, giving it strength and durability in its journey up and down hills, causing items to shift less and placing less strain on the body itself. With the spreading white hemp cover resembling sails, it is no wonder these conveyances were known as Prairie Schooners. The swooping boat shape may have contributed to this name as well. They were not, in fact, despite popular myth, designed this way so they could serve as boats when crossing waterways. There was no way they would have been sealed tight enough to withstand a water crossing. Even so, there were numerous shallow streams to be crossed on the way to Indiana.

Our family would of course pack tools such as handsaws, hammers, augers, broad axes, cross cut saws and chisels. A list of sundry articles that would be packed on the wagon might also include thread, thimbles, pins, needles, snaffle bits, spurs and bed cords. Our family would have loaded only the most basic of necessities, perhaps taking care to wrap some treasured heirloom in an old quilt if there was room. Furniture could be made when they reached their destination. Seeds would be carefully wrapped in paper to start a garden in their new home. There was not room for passengers and only the elderly and infirm would have ridden. Everyone else walked and it is just as well, for even after the improvement of the National Road, it was a bumpy ride.

The horses that drew their wagon were heavier than saddle horses, with proportions more similar to a draft horse, large and muscular perhaps akin to the Suffolk Punch or Belgian. The Conestoga horse never became a real breed in the truest sense of the word, as farmers bred their mares to the best stallion available and when sires of pure draft breeds were available, they were certain to be preferred. So it was likely the so-called “Conestoga draft horse” was a mongrel, bred from no particular breed, but bred in and of itself for stamina and endurance, heavy enough for strength and light enough for dexterity on the treacherous early roads. They were rarely stabled, but rested in the wagon yards of the old taverns at night. They were fed in troughs suspended on the back of the wagons. Oxen, though slower, had far more staying power and were often used in teams of up to a dozen oxen. The teamster or driver rode in a specially constructed saddle on the back “near” or left wheel horse. In the case of oxen, he walked near the back near ox. Whether oxen or horses, these animals were steady and reliable and accustomed to following voice commands such as gee (right) and haw (left). Horses were also controlled through the use of a single rein called a “jerk line” that led from the near leader and passed through the bridle of the near middle leader to the near wheel horse. One wagoner said, “A good leader you just speak to; a line is for safety.”

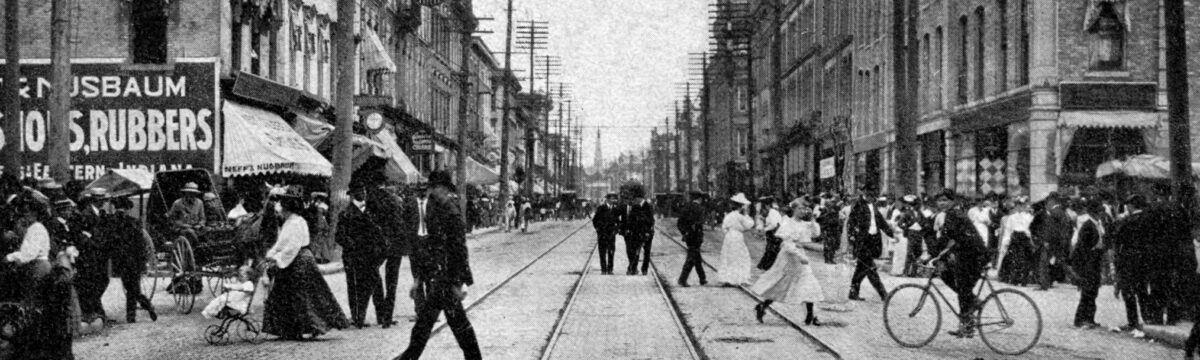

When the wagon rolled into Wayne County, they might have stopped along the way at the Huddleston’s farmhouse in Cambridge City. They may have stopped to buy some ground corn at Jeremiah Cox’s grist mill. Perhaps they replenished their supplies at John Smith’s store set up in a log cabin on South Second and B Streets. If they wished to mail news back home of their safe arrival, they could go to the post office at the corner of Main and Front. Until 1829, Robert Morrisson was the postmaster and he later established the Morrisson Library in 1864. Mail arrived every two weeks, weather permitting.

The covered wagon was an enduring symbol of the westward journey. It was a bone-jarring, tooth rattling excursion on the National Road that stood out in sharp contrast to the ride we now enjoy on U.S. 40 for which we all can be immensely thankful.

— Gretchen Brown

Sources:

The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. 2016

Luther Feeger, Palladium-Item, 1953

The Old Pike – An illustrated Narrative of the National Road by Thomas B. Searight

http://www.waynet.org/facts/history.htm

Thanks also to Jim Harlan, Director of the Wayne County Historical Museum