Stagecoaches – Icons of Westward Travel

Later in the life of the National Road when the surface was improved, stagecoaches made their way into Richmond. Let us imagine a traveler on her way from Washington to Richmond to perhaps join her husband here. She would, of course, according to protocol of the time, have to be escorted by a man, if not her husband, then her brother or grown son. If this traveler were to get on a stage at Washington, she had a long, bumpy ride of several days before her stage at last rolled into Richmond. According to The Richmond Palladium of the time, if you rode a coach, you could expect to get from Washington to Wheeling in about thirty hours, to Columbus in forty-five and to Indianapolis in sixty. It did not specify if that included layovers at inns on the way, or any other necessary stops to rest the horses or change wheels and make repairs. Some said it took eighteen hours to reach Cincinnati from Richmond, but that this was later cut by half, perhaps as a result of the roads being improved.

Stagecoaches and Conestoga wagons, interestingly enough, shared a common ancestor: the baggage wagon. Stagecoaches coming down the Old Pike into Richmond were of two kinds. There was the Concord, made in Concord, New Hampshire, weighed a ton or more and were made with a leather belt suspension system, called thoroughbraces, which gave a swaying motion from side to side, as opposed to a jolting up and down. One wonders that the passengers were not affected by severe motion sickness! Then there was the lowly mudwagon, or celerity wagon, in appearance not that much different from the coach. It was lighter, but provided a far bumpier ride. They were less costly, but typically used for the shorter runs. One passenger described a journey on one of these thus: “As for sleeping, most of the wagons are arranged so that the backs of the seats let down and form a bed the length of the vehicle. When the stage is full, passengers must take turns at sleeping. Perhaps the jolting will be found disagreeable at first, but a few nights without sleeping will obviate that difficulty, and soon the jolting will be as little of a disturbance as the rocking of a cradle to a sucking babe. For my part, I found no difficulty in sleeping over the roughest roads, and I have no doubt that anyone else will learn quite as quickly. A bounce of the wagon, which makes one’s head strike the top, bottom, or sides, will be equally disregarded, and “nature’s sweet restorer” found as welcome on the hard bottom of the wagon as in the downy beds of the St. Nicholas. White pants and kid gloves had better be discarded by most passengers.” Our hypothetical passenger was by now likely not only very tired, but dusty and dirty as well. Travel on the stagecoaches of the time was primitive and uncomfortable. There were no doors on the early coaches, so even ladies were obliged to climb out the window over the driver’s seat. There was no glass in these windows as it would only get broken over the constant jolting over the rough roads and the constant flexing of the coach body. Instead there were leather or canvas curtains that could be rolled down in inclement weather. The coaches could accommodate as many as nine passengers, with six more on top. In an age where a certain amount of prudishness was the rule, passengers were obliged to interlock knees in the lack of foot room or rest a head on the shoulder of a complete stranger. It is no wonder that ladies were required to travel accompanied!

You could only bring twenty-five pounds of luggage with you and this was stowed away in what was called the “boot”, that term still being used today for the trunk of a car in Britain. The mail might be carried in the front boot, though Mark Twain recalled it being equally likely to be shoved among the already cramped feet of the passengers. For ladies, with their numerous accoutrements of the time, it would be difficult, if not impossible to pack under twenty-five pounds.

As a mail coach approached a town, a fresh team of horses was brought out and the road-weary team was changed out with startling rapidity, buckles undone, straps loosened and soon a new team was ready to go. The roads were hard on the poor stagecoach horses, giving them a condition known at the time as “sprung knees”, probably caused by the strain of going down the steep grades on some parts of the National Road.

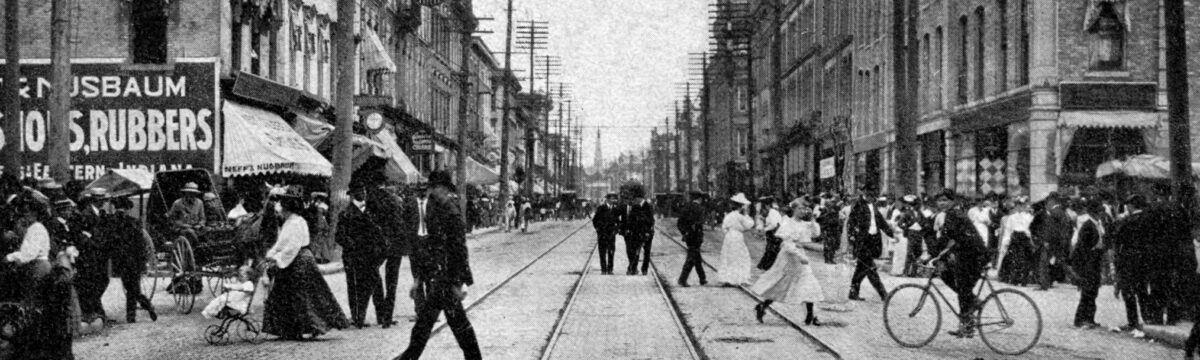

Very little comes down to us in the present day about the actual men who drove the stagecoaches. One name at least is preserved through the writing of a one-time Morrisson-Reeves librarian, Mrs. Sarah Wrigley who remembers a favorite Richmond driver by the name of Dan Custer. He must have been a friendly one, for he made friends with all the boys in the community. A horn was blown as the stagecoach drivers approached the Main Street Bridge in Richmond, warning unwary pedestrians to get out of the way. Most coach drivers were under forty years of age as the life of a driver was not for the faint of heart. When the weather turned cold and frigid, he was exposed to all elements. There is a story told of one whose horses and conveyance arrived at a tavern, but the driver himself was found in his seat, to have died of exposure. They were required to be able to change their horses for fresh, quickly and the manipulation of the harness required nimble fingers. In Stagecoach and Tavern Tales of the Old Northwest, he was described thus: “In speech he was more picturesque than grammatical…” He was most often dressed in rough corduroy breeches, boots and a fur or leather coat against the winter wind. At the arrival of a stagecoach at a stop, if a meal was not to be taken, the horses were quickly changed out for a new set of four. At regular intervals, between horse changes, they were watered, fed and curried. Also, oil was rubbed into the harness, the coach washed and the wheels greased. There was much competition between stage drivers, sometimes verging on unruly practices. In addition, the remote parts of the National Road provided a perfect opportunity for highwayman. For this reason, many stage coach lines employed heavily armed guardsmen.

The Main Street Bridge, in use from 1834 to 1895, could have only been a very welcome sight for our dusty, sore and weary traveler. She would have climbed down from the coach and had someone gather up her trunk with all her belongings. Perhaps she would join her husband at one of the accommodations in town or perhaps she would have stayed further on in Centerville at the graciously appointed Mansion House or the Vinton House in Cambridge City.

— Gretchen Brown

Sources:

Thomas B Searight’s The Old Pike – An Illustrated Narrative of the National Road ed. Joseph E. Morse and R. Duff Green

Luther M. Feeger Palladium Item

Dictionary of American History | 2003

The Butterfield Overland Mail by Waterman L. Ormsby