The High Point Hotel was a grand structure situated at the top of the hill where North E Street (or Grand Boulevard) ends at the entrance to Glen Miller Park. It was bult with great fanfare, but never found success. It fell into disrepair and was torn down barely 13 years after it opened.

In 1890, promoters Omar Hittle, Richard Jackson, and Daniel G. Reid opened up a new subdivision known as Grand Boulevard, encompassing roughly North 20th through 24th, and North D to the railroad. To make the area even more appealing, they convinced the City of Richmond to lease an acre of the park to them, and to build a huge summer hotel that would draw travelers from around the state to the park. The lease was signed in April 1890 on the condition that the hotel would be built in a year.

Local architect William S. Kaufman designed the sprawling, three story building, complete with four squared towers on its corners and an elevated veranda that wrapped around three sides. Kaufman was one of Richmond’s most famous architects, perhaps second only to John Hasecoster. Kaufman came to Richmond in 1884 to superintend the construction of Eastern Indiana Hospital for the Insane, now known as Richmond State Hospital. He specialized in public buildings, and was responsible for hundreds of schools across the region, including Richmond’s High School constructed in 1910 on North 9th Street (now known as Ace USA Insurance), St. Andrew School, and Joseph Moore Elementary. On Earlham’s campus, he designed Lindley, Parry and Bundy Halls. He superintended the construction of the Wayne County Courthouse, as well as the Fayette County Courthouse.

The building was completed in the spring of 1891, but never opened as a hotel. It’s not clear why, although some believed that it was simply too far away from the city.

In early 1892 doctors associated with the Nixon Treatment for consumption (today known as tuberculosis) leased the hotel and turned it into a sanitarium. Dr. John Nixon claimed he could cure the disease by having patients breath medicated steam. In this case, Its location far from the city was an advantage. In May 1892 the papers claimed that High Point would “be a Mecca” for consumption sufferers from across the state and region. The hospital would “be bound to advertise the city to the world, and will be the means of bringing thousands of dollars to Richmond that would otherwise remain away. The institution already employs fifteen people.”

It only took a few weeks, however, to realize that this was a bad move. Yes, it was far from the city, but it was basically inside the park. Consumption was contagious and, at that point, incurable, no matter what Dr. Nixon asserted. Having a concentration of consumptives in such close proximity to the park that the rest of Richmond used for relaxation and recreation was a terrible idea. An article from August 20 described the situation in especially florid 19th century language:

The patients expectorate upon pieces of cotton, paper or rags, which are thrown out of the windows and blown by the wind all over the grounds; and thus these original packages of mucus laden with the bacillus of consumption in all stages of virulence are put into excellent circulation. Not only that, all kinds of offal is wrapped in papers and thrown out of the windows to spread contagion and offend the eyes and noses of people who go to the glen for rest.

Richmond Item, August 20, 1892

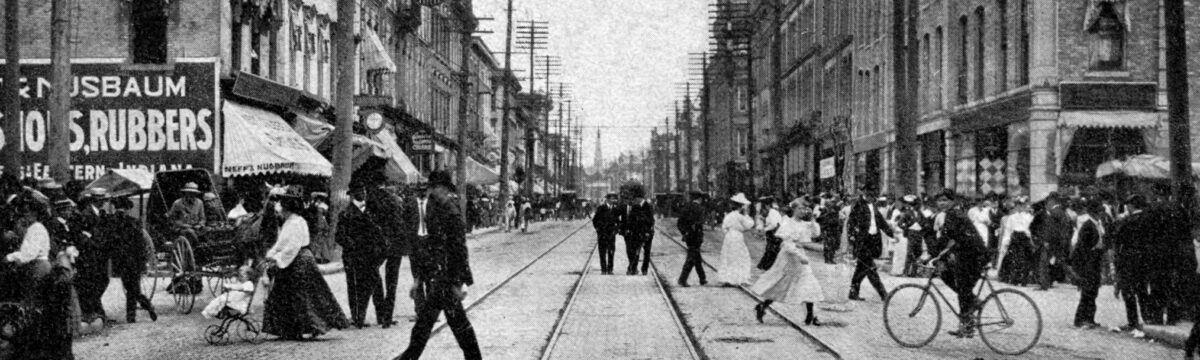

A few days later, the hospital closed, and the following month the building was leased for the Wilke Art School, run by Mr. and Mrs. Fred Wilke. (see photo at the start of this post) This enterprise was also unsuccessful, and the building was sold in March 1894. In August 1894, Richmond welcomed a branch of the Keeley Institute. Founded by Leslie Keeley in 1879, the institute was a program that claimed it cured alcoholism. At its height it had more than 200 branches. Unfortunately, within a few months it was evident that the sprawling hotel was too large for Richmond’s branch, and it vacated in May 1895.

Over the next several years, it was largely unoccupied. It hosted a handful of special events, such as dances and reunions, but even though it was sold to new promoters a couple times, each of whom claimed they were going to fix it up and make it a destination, the building fell into disrepair. By 1903, the papers referred to it as an eyesore.

In July 1904 demolition began, but it was such a huge building that it wasn’t until November that the last remains were cleared away. Soon after, the park commissioners reincorporated the land back into Glen Miller Park.