One hundred years ago Richmond was dealing with the so-called Spanish Flu. The rest of the world was dealing with it as well, which made it a true pandemic. The story of this particular influenza strain is tied to the story of the World War. What might have been a harsher than usual flu outbreak, was inflated into a worldwide pandemic by many factors.

The first recorded case of this flu occurred in the southwest part of Kansas in the winter of 1918, and it might have stayed there had it not been for the young men from that area who reported for duty to Camp Funston, Kansas. The United States had declared war the previous April, but the Army still relied on hastily constructed and overcrowded camps for training the new recruits. Thousands of young men with no natural immunity to the flu crowded into less-than-sanitary tents and barracks, which were an ideal breeding ground for any disease, and especially the flu. It swept through the entire military as the soldiers moved to other camps for training, and it traveled with it to Europe where it infected soldiers on both sides of the trenches.

This was only the first wave, however. Huge numbers of men were sickened, but relatively few died. By the late summer of 1918, the flu had mutated to a much more severe form, and this wave escaped the military bases and infected the civilian population. This was the wave that was responsible for the vast majority of the influenza deaths, and most of those deaths occurred in just two months — October and November 1918. It was made all the more terrifying with the speed at which it killed — in many cases a victim went from feeling fine to dead in a matter of hours – and, unlike most flu outbreaks which kill the very young and the very old, this strain was especially hard on young adults in the prime of health.

In 1918, little could be done to treat the flu once contracted. Doctors at the time believed its cause to be bacterial and searched for a vaccine, but since it is caused by a virus, none of the resulting vaccines proved effective. Often it was the resulting bacterial pneumonia that was fatal, but antibiotics were not discovered yet. The only way to prevent the spread was to prevent the transmission between people. One method was to wear gauze masks, and Red Cross units began making these masks in huge numbers. The other was to prevent people from gathering in large groups, basically a quarantine.

The “influenza ban” began on October 7 and originally it was to end on October 20th. As numbers of reported flu cases continued to climb, that date was postponed. Dr. J. M. Bulla was the Wayne County Health Officer, and by October 11 he estimated that there were between 200 and 300 cases in the county, but it was difficult to be more precise because of lax reporting. Dr. T. Henry Davis, Richmond’s Health Officer, reported the next day that there were about 100 cases in the city. Trained medical personnel were in short supply, because many had joined the military, so calls went out for volunteers to help nurse the sick.

Closing all the churches was a bit controversial; in some cities clergymen argued that attending church brought comfort in stressful time. In Richmond it seemed like all the churches complied. On Sundays the Richmond Item published short sermons written by local clergy, so that individual families could still worship in their homes.

By the end of October the number of new cases had dropped to acceptable levels, and the ‘ban’ was lifted at midnight, Saturday, November 2, and the next morning, churches opened for the first time in 3 weeks. The school superintendent announced that the school year would be divided into two 16-week semesters instead of 18-week ones. All seemed to be getting back to normal until November 11.

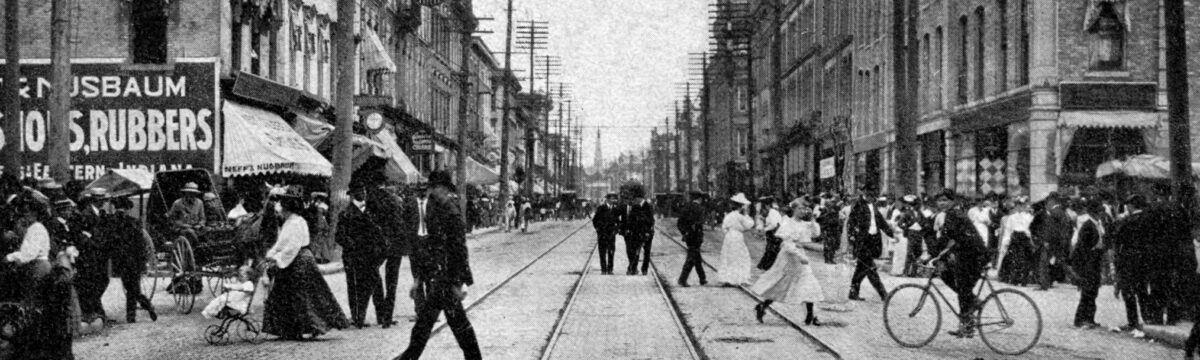

The war officially ended at 11:00 AM on the 11th day of the 11th month, and millions of people in the warring nations spontaneously poured into the streets to celebrate — the opposite of the ‘flu ban.’ Within days, influenza cases reappeared, and on November 18, Wayne County’s flu ban was reimposed, and lifted on December 1.

Approximately 100 people in Richmond died during the last three months of the year. In several instances, whole families were stricken and in several cases, more than one family member died. Florence Ryan, 33, died on October 17, and her 4-year-old daughter, Mary, died on November 2. 33-year-old Everett Reynolds died on November 24, just a week after his 2-year-old son.