As anyone who has viewed the recent PBS American Experience documentary “The Great War” knows, the Harlem Hellfighters was the nickname of the 369th Infantry Regiment. It was an African-American regiment from New York City that distinguished itself with the French army in the early months of 1918. The documentary does a great job telling the history of the unit, but it leaves out one detail that connects the story to Richmond, Indiana.

In addition to fame in battle, the 369th was known for its regimental band. The band was led by New York musician and composer James Reese Europe. He was determined to have a first class ensemble filled with at least 50 professional musicians, more than the prescribed 28 members of a normal Army marching band. He figured that the sum needed to pay and equip such a band was $10,000, a huge amount of money in those days. The regiment’s commander, Col. William Hayward, was just as determined to provide for this band and went about securing funds.

Hayward related the story to his adjutant, Capt. Arthur Little, who included it in his book of 1936, From Harlem to the Rhine.

In a spirit almost of despair, I called upon Mr. Daniel Reid, sometimes described as The Tin Plate King, or American Can King.

I told my story to Dan Reid, and he was very nice, gave me all the time I wanted, and said, “What do you want me to do?”

I said, “I’d like to have you give me letters of introduction to 30 or 40 of your rich friends, and ask them to let me talk to them, and then if they will let me talk to them, I am going to try and touch them for $500 a piece.”

Dan Reid said to me, “How many of the 30 or 40 victims do you expect to land for $500 a piece?” I said I hoped to land at least 20 of them

Mr. Reid reached into a drawer of his desk, took out his check book, and wrote me a check for $10,000 and said, “That’s a damn sight easier than writing you 40 letters of introduction, and it will save you a lot of time, too. Here are your 20 victims at $500 each.”

As soon as the regiment arrived in France, the band began giving concerts at army camps and hospitals, and it was widely reported that the music it provided was a huge boost to morale.

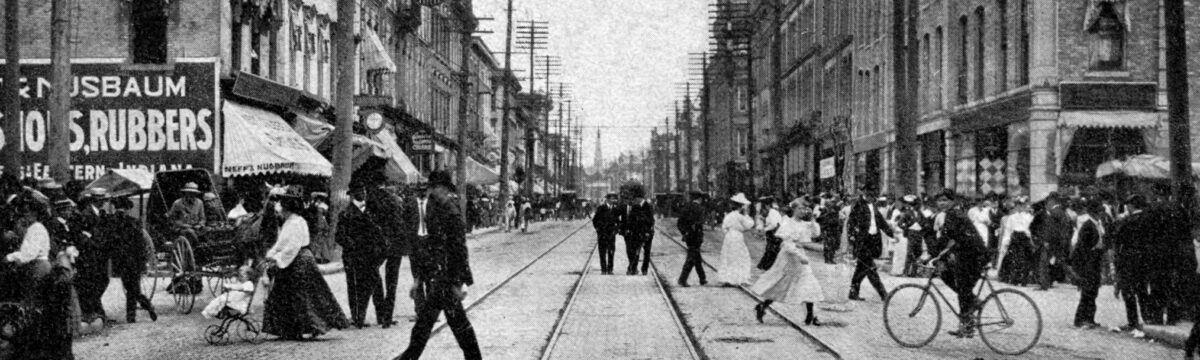

From the New York Public Library Digital Collections

In a letter to a friend in New York, Col. Hayward described the effect on audiences. The letter was reprinted in newspapers around the country, including the Richmond Palladium on April 23, 1918.

Our band is the most wonderful thing over here. I don’t believe any money ever bought as much pleasure and happiness for human beings as did Daniel G. Reid’s in this instance. If Mr. Reid could see tired, exhausted men straighten up, shift packs a little higher and step like school kids when they play, or see the thin, wan faces lean out of hospital windows to catch every note of melodious cheer of Southern melody or the sextette from “Lucia,” he would be pleased with his investment. If I’ve told one officer I’ve told a thousand of his wonderful generosity in the matter, and everybody who knows of the band knows how it started.

For those who may not know, Daniel Gray Reid (1858-1925) was a successful industrialist, Wall Street financier, and railroad magnate, who had grown up in Richmond, Indiana. Even though he moved from Richmond in the early 1890s he always considered it his home, and lavished huge amounts of money in donations over the years. He built the first building of Reid Hospital as a memorial to his wife and son, and that small hospital grew over the years to the complex that has now been abandoned, but his name still graces the institution.

— Sue King